When I first started using styled-components, it seemed like magic ✨.

Somehow, using an obscure half-string-half-function syntax, the tool was able to take some arbitrary CSS and assign it to a React component, bypassing the CSS selectors we've always used.

Like so many devs, I learned how to use styled-components, but without really understanding what was going on under the hood.

Knowing how it works is helpful. You don't need to understand how cars work in order to drive, but it sure as heck helps when your car breaks down on the side of the road.At least, I assume it does? I don't actually know how cars work 😅

Debugging CSS is hard enough on its own without adding in a layer of tooling magic! By demystifying styled-components, we'll be able to diagnose and fix weird CSS issues with way less frustration.

In this blog post, we'll pop the hood and learn how it works by building our own mini-clone of 💅 styled-components.

Link to this headingThe big idea

Let's start with a minimal example, taken from the official docs:

const Title = styled.h1`

font-size: 1.5em;

text-align: center;

color: palevioletred;

`;styled-components comes with a collection of helper methods, each corresponding to a DOM node. There's h1, header, button, and dozens more (they even support SVG elements like line and path!).

The helper methods are called with a chunk of CSS, using an obscure JavaScript feature known as “tagged template literals”. For now, you can pretend that it's written like this:

const Title = styled.h1(`

font-size: 1.5em;

text-align: center;

color: palevioletred;

`);h1 is a helper method on the styled object, and we call it with a single argument, a string.

These helper methods are little component factories. Every time we call them, we get a brand-new React component.

Let's sketch this out:

// When I call this function…

function h1(styles) {

// …it generates a brand-new React component…

return function NewComponent(props) {

// …which will render the associated HTML element:

return <h1 {...props} />

}

}When we run const Title = styled.h1(...), the Title constant will be assigned to our NewComponent component. And when we render the Title component in our app, it'll produce an <h1> DOM node.

What about the styles parameter that we passed to the h1 function? How does it get used?

When we render the Title component, a few things happen:

- We come up with a unique class name by hashing

stylesinto a seemingly-random string, likedKamQWoriOacVe. - We run the CSS through Stylis, a lightweight CSS preprocessorSimilar to Sass/Less, it applies vendor prefixes as-needed, and offers a few quality-of-life perks.

- We inject a new CSS class into the page, using that hashed string as its name, and containing all of the CSS declarations from the

stylesstring. - We apply that class name to our returned HTML element

Here's what that looks like in code:

function h1(styles) {

return function NewComponent(props) {

const uniqueClassName = comeUpWithUniqueName(styles);

const processedStyles = runStylesThroughStylis(styles);

createAndInjectCSSClass(uniqueClassName, processedStyles);

return <h1 className={uniqueClassName} {...props} />

}

}If we render <Title>Hello World</Title>, the resulting HTML will look something like this:

<style>

.dKamQW {

font-size: 1.5em;

text-align: center;

color: palevioletred;

}

</style>

<h1 class="dKamQW">Hello World</h1>Link to this headingLazy CSS Injection

In React, it's common to render some JSX conditionally. In this example, we only render our <Wrapper> element if our ItemList component is given some items:

Code Playground

import styled from 'styled-components'; function App() { return <ItemList items={[]} />; } function ItemList({ items }) { if (items.length === 0) { return 'No items'; } return ( <Wrapper> {/* Stuff omitted */} </Wrapper> ) } const Wrapper = styled.ul` background: goldenrod; `; export default App;

It may surprise you to learn that styled-components doesn't do anything with the CSS we provided in this case. That background declaration is never added to the DOM.

Instead of eagerly generating CSS classes whenever a styled component is defined, we wait until the component is rendered before injecting those styles into the page.

This is a good thing! On larger websites, it's not uncommon for hundreds of kilobytes of unused CSS to be sent to the browser. With styled-components, you only pay for the CSS you render, not the CSS you writeTechnically, some unused CSS will still wind up in the JS bundle, but when we're server-side-rendering, that's a worthwhile tradeoff: we can paint the page before we receive the JS, but not before we receive the CSS..

The only reason this works is because JavaScript has closures. Every component generated from styled.h1 has its own little scope that holds the CSS string. When we render our Wrapper component, even if it's seconds/minutes/hours later, it has exclusive access to the styles we've written for it.

There's one more reason that we defer CSS injection: because of interpolated styles. We'll cover those near the end of this article.

Link to this headingDynamically adding CSS rules

You might be wondering: how does that createAndInjectCSSClass function work? Can we really generate new CSS classes from within JS?

We can! One straightforward way is to create a <style> tag, and then fill it with raw CSS text:

const styleTag = document.createElement('style');

document.head.appendChild(styleTag);

const newRule = document.createTextNode(`

.dKamQW {

font-size: 1.5em;

text-align: center;

color: palevioletred;

}

`);

styleTag.appendChild(newRule);This method works, but it's cumbersome and slow. A more modern way to do this is with the CSSOM, the CSS version of the DOM. The CSSOM provides a friendlier way to add or remove CSS rules using JavaScript:

const styleSheet = document.styleSheets[0];

styleSheet.insertRule(`

.dKamQW {

font-size: 1.5em;

text-align: center;

color: palevioletred;

}

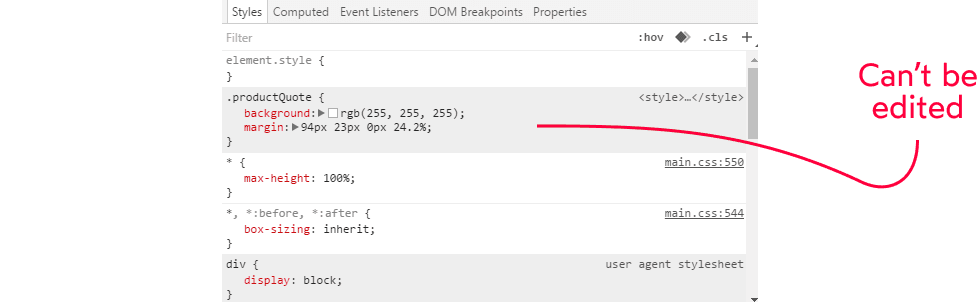

`);For a long time, styles generated through the CSSOM couldn't be edited in the Chrome developer tools. If you've ever seen "greyed out" styles in the devtools, it's because of this limitation:

Thankfully, however, this changed in Chrome 85. If you're interested, the Chrome team wrote a blog post(opens in new tab) about how they added support for CSS-in-JS libraries like styled-components to the devtools.

Link to this headingGenerating helpers with functional programming

Earlier, we created an h1 factory function to emulate styled.h1:

function h1(styles) {

return function NewComponent(props) {

const uniqueClassName = comeUpWithUniqueName(styles);

const processedStyles = runStylesThroughStylis(styles);

createAndInjectCSSClass(uniqueClassName, processedStyles);

return <h1 className={uniqueClassName} {...props} />

}

}This works, but we need many many more helpers! We need buttons and links and footers and asides and marquees.

There's another problem, too. As we'll see, styled can be called as a function directly:

const AlternativeSyntax = styled('h1')`

font-size: 1.5em;

`);The styled object is both a function and an object. Bewilderingly, this is a totally valid thing in JavaScript. We can do stuff like this:

function magic() {

console.log('✨');

}

magic.hands = function() {

console.log('👋')

}

magic(); // logs '✨'

magic.hands(); // logs '👋'Let's update our styled-components clone to support these new requirements. We can borrow some ideas from functional programming to make it possible.

const styled = (Tag) => (styles) => {

return function NewComponent(props) {

const uniqueClassName = comeUpWithUniqueName(styles);

createAndInjectCSSClass(uniqueClassName, styles);

return <Tag className={uniqueClassName} {...props} />

}

}

styled.h1 = styled('h1');

styled.button = styled('button');

// ...And so on, for all DOM nodes!This code uses a technique known as currying. It allows us to "preload" the Tag argument.

If you haven't seen it before, currying can be a bit mindbending. But it's helpful in this case, as it allows us to easily create many shorthand helper methods:

// This:

styled.h1(`

color: peachpuff;

`);

// …is equivalent to this:

styled('h1')(`

color: peachpuff;

`);For more information on currying, check out this lovely blog post(opens in new tab) by Aphinya Dechalert.

Link to this headingWrapping custom components

One of the coolest things about styled-components is that we can mix them with our own custom components!

Here's an example:

Code Playground

import styled from 'styled-components'; function Message({ children, ...delegated }) { return ( <p {...delegated}> You've received a message: {children} </p> ); } const UrgentMessage = styled(Message)` background-color: pink; padding: 8px; `; function App() { return ( <UrgentMessage> We're having a fire sale! </UrgentMessage> ); } export default App;

At first glance, this seems absolutely magical. How are we applying those styles to our custom component?

The key is in the prop delegation. Here's what we'd see if we logged out that delegated object:

function Message({ children, ...delegated }) {

console.log(delegated);

// { className: 'OkjqvF' }

return (

<p {...delegated}>

You've received a message: {children}

</p>

);

}Where's that className coming from? Well, we create it inside our styled helper!

const styled = (Tag) => (styles) => {

return function NewComponent(props) {

const uniqueClassName = comeUpWithUniqueName(styles);

createAndInjectCSSClass(uniqueClassName, styles);

return <Tag className={uniqueClassName} {...props} />

}

}Here's the order of operations:

- We render

UrgentMessage, a styled component that composes theMessagecomponent. - We come up with a unique class name (

OkjqvF), and render theTagvariable (ourMessagecomponent) with aclassNameprop. Messagegets rendered, passing theclassNameprop to the<p>element

This only works if we apply the className prop to an HTML node inside our component though. The following won't work:

function Message({ className, children }) {

/*

Because we're ignoring the `className` prop,

the styles will never be set.

*/

return (

<p>

You've received a message: {children}

</p>

);

}By delegating all of the props that Message receives to the <p> element it renders, we unlock this pattern. Thankfully, many third-party components (eg. the Link component in react-router) follow this convention.

Link to this headingComposing styled-components

In addition to wrapping our own components, we can also compose styled-components together.

For example:

Code Playground

import styled from 'styled-components'; const Button = styled.button` background-color: transparent; font-size: 1.5rem; `; const PinkButton = styled(Button)` background-color: pink; `; function App() { return ( <PinkButton> Hello World </PinkButton> ); } export default App;

I used to think that the library "merged" these styles somehow, creating a new "mega class" that contained all the declarations. But it actually creates two distinct classes.

If we check out the HTML/CSS generated, it would look something like this:

<style>

.abc123 {

background-color: transparent;

font-size: 1.5rem;

}

.def456 {

background-color: pink;

}

</style>

<button class="abc123 def456">Hello World</button>Our goal in this process is to make sure that the PinkButton styles "extend" Button styles. In the event of a conflict, PinkButton should win.

Rather than overcomplicating things in JavaScript, we can rely on CSS to do the hard work for us!

In CSS, there is a complex hierarchy of rules that governs how to resolve conflicts. An ID selector, #btn, will win out against a class selector, .btn. Which in turn beats a tag selector, button.

But in this case, we have two classes! The two selectors, .abc123 and .def456, are equally matched. So the algorithm falls back to a secondary rule: it looks at the order of rules defined in the stylesheet.

An important clarification: The order that we apply the classes doesn't matter. Consider this case:

Code Playground

HTML

CSS

Result

Notice that both paragraphs are blue, despite the fact that we've flipped the order of the listed classes in the second paragraph!

In CSS, the order of the classes in the class property is irrelevant. The only thing that matters is the order of the style rules within the <style> tag (or in linked CSS files).

The styled-components library takes great care to ensure that CSS rules are inserted in the correct order, to make sure that the styles are applied correctly. This is a non-trivial problem: we do all kinds of dynamic things in React, and the library is constantly adding/removing classes, while ensuring that a sensible order is preserved.

Alright, let's keep working on our styled-components clone.

We need to update our code so that it applies both of the classes. We can combine them like so:

const styled = (Tag) => (styles) => {

return function NewComponent(props) {

const uniqueClassName = comeUpWithUniqueName(styles);

const processedStyles = runStylesThroughStylis(styles);

createAndInjectCSSClass(uniqueClassName, processedStyles);

const combinedClasses =

[uniqueClassName, props.className].join(' ');

return <Tag {...props} className={combinedClasses} />

}

}When we render PinkButton, the Tag variable is equal to our Button component. PinkButton will generate a unique class name (def456), and pass that as the className prop to Button.

If you're confused by this process, you're not alone; we've entered the mindbending realm of recursion, where styled-components are rendering styled-components. As I wrote this article, I tripped over this bit, and had to spend a minute reconfiguring my own understanding.

But here's the thing: the exact JS mechanics that accomplish this aren't important. That's an implementation detail. The important thing is that you understand these takeaways:

- When we render

PinkButton, we're also renderingButton. - Each styled component will produce a unique class, like

abc123ordef456. - All of the classes will be applied to the underlying DOM node.

- styled-components makes sure to insert these rules in the correct order, so that

PinkButton's styles will overwrite any conflicts inButton.

Link to this headingInterpolated styles

We've almost finished creating our minimum-viable styled-components clone, but there's one more task in our list: .

Sometimes, our CSS will depend on React props. For example, an image might take a maxWidth prop:

Code Playground

import styled from 'styled-components'; function App() { return ( <> <ContentImage alt="A running shoe with pink laces" src="/img/shoe.png" maxWidth="200px" /> <ContentImage alt="A close-up shot of the shoe" src="/img/shoe-closeup.png" /> </> ); } const ContentImage = styled.img` display: block; margin-bottom: 8px; width: 100%; max-width: ${p => p.maxWidth}; `; export default App;

Here's what our DOM looks like, after rendering these images:

<style>

.JDSLg {

display: block;

margin-bottom: 8px;

width: 100%;

max-width: 200px;

}

.eXyedY {

display: block;

margin-bottom: 8px;

width: 100%;

}

</style>

<img

alt="A running shoe with pink laces"

src="/img/shoe.png"

class="sc-bdnxRM JDSLg"

/>

<img

alt="A close-up shot of the shoe"

src="/img/shoe-closeup.png"

class="sc-bdnxRM eXyedY"

/>The first class, sc-bdnxRM, is used to uniquely identify the React component that was rendered (ContentImage). It doesn't provide any styles, and we can ignore it for our purposes.

The interesting thing is that each image is given a completely unique class!

The seemingly-random class names, JDSLg and eXyedY, are actually hashes of the styles that will be applied. When we interpolate in a different maxWidth prop, we get a different set of styles, and so a unique class is generated.

This explains why we can't "pre-generate" the classes! We have to wait until the component is rendered before we know what CSS will be applied, because the same styled.img instance won't always produce the same styles.

Interpolation isn't the only way we can customize the styles of one particular component instance. My personal favourite way is to use CSS variables. It looks like this:

Code Playground

import styled from 'styled-components'; function App() { return ( <> <ContentImage alt="A running shoe with pink laces" src="/img/shoe.png" // 👇 No more interpolated styles! style={{ '--max-width': '200px', }} /> <ContentImage alt="A close-up shot of the shoe" src="/img/shoe-closeup.png" /> </> ); } const ContentImage = styled.img` display: block; margin-bottom: 8px; width: 100%; max-width: var(--max-width); `; export default App;

If we inspect the HTML, we'll notice that both elements share the same CSS class:

<style>

.JDSLg {

display: block;

margin-bottom: 8px;

width: 100%;

max-width: var(--max-width);

}

</style>

<img

alt="A running shoe with pink laces"

src="/img/shoe.png"

class="sc-bdnxRM JDSLg"

style="--max-width: 200px;"

/>

<img

alt="A close-up shot of the shoe"

src="/img/shoe-closeup.png"

class="sc-bdnxRM JDSLg"

/>By letting modern CSS do the dynamic stuff for us, we produce less CSS. This is also a potential performance win: when the dynamic data changes, we don't need to generate a whole new CSS class and append it to the page!That said, styled-components is a highly-optimized library, and this isn't likely to make a noticeable difference in most circumstances.

I wrote about this pattern (and many others!) in my blog post, “The styled-components Happy Path”.

Link to this headingCorrecting the record

Remember earlier, when I said you could think of these two things as equivalent?

const Title = styled.h1`

font-size: 1.5em;

text-align: center;

color: palevioletred;

`;

const Title = styled.h1(`

font-size: 1.5em;

text-align: center;

color: palevioletred;

`);When we start supporting interpolations, they stop being equivalent.

Tagged template literals are wild, and it would take an entirely separate blog post to explain how they work and what they're doing here.

The important thing to know is that all of those little interpolation functions are called when the component is rendered, and used to "fill in the gaps" in our style string.

Here's a quick sketch:

const styled = (Tag) => (rawStyles, ...interpolations) => {

return function NewComponent(props) {

/*

Compute the styles from the template string, the

interpolation functions, and the provided React props.

*/

const styles = reconcileStyles(

rawStyles,

interpolations,

props

)

/* The rest is unchanged: */

const uniqueClassName = comeUpWithUniqueName(styles);

const processedStyles = runStylesThroughStylis(styles);

createAndInjectCSSClass(uniqueClassName, processedStyles);

const combinedClasses =

[uniqueClassName, props.className].join(' ');

return <Tag {...props} className={combinedClasses} />

}

}When we render our component, reconcileStyles is able to invoke each of those interpolated functions with the data passed through props. In the end, we're left with a plain ol' string with populated values.

When the props change, the process is repeated, and a new CSS class is generated.

Link to this headingGood golly, you made it to the end!

This blog post has been a journey. Perhaps more than any other post I've written, this one covers some pretty treacherous terrain. This stuff is not easy to wrap our mind around.

If parts of this post didn't make much sense to you, that's alright! It might require a bit of percolation. As you continue to use styled-components, hopefully the ideas in this post will become clear.

In addition to the practical benefits of understanding your tools, I hope that this post also helps you appreciate what the styled-components team has accomplished. Building and maintaining open-source software is never easy, and it's especially fraught when working on a CSS-in-JS tool, in a community where the entire category is contentious.

If you found this post helpful, you might be interested in something else I've released. It's called CSS for JavaScript Developers(opens in new tab). It's a comprehensive online course specifically created for developers who use JS frameworks like React, and who find CSS confusing or frustrating. We learn exactly how CSS works as a language, from first principles, building a robust mental model that can be used to solve just about every layout challenge you encounter. We use styled-components as our tool of choice.

You can learn more about the course here:

Special thanks to Phil Pluckthun(opens in new tab) and Max Stoiber(opens in new tab) for reviewing this blog post.

Last updated on

November 17th, 2024